Precipitation whiplash

and climate change threaten

California’s freshwater

Almost two-thirds of California’s freshwater originate in the Sierra Nevada mountains. But the source is in trouble.

Imagine the snow in the Sierra Nevada mountains as a giant reservoir providing water for 23 million people throughout California. During droughts, this snow reserve shrinks, affecting water availability in the state.

Snow extent on April 1

Redding

Sacramento

San Francisco

Los Angeles

San Diego

Researchers fear global warming will cause the Sierra Nevada snowpack to lose much of its freshwater by the end of the century, spelling trouble for water management throughout the state.

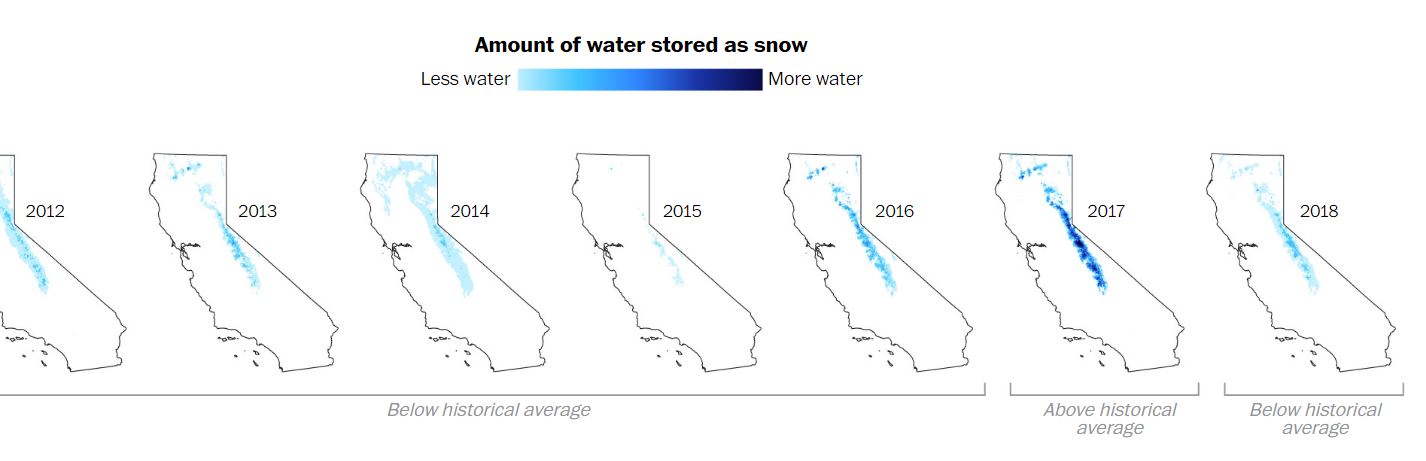

The California Department of Water Resources found last month that the water content in the Sierra snowpack was about half its historical average for the beginning of April despite late winter storms. One year before, the water content had been measured at over 160 percent of the historical average. This swing is not new and continues California’s recent trend of climate shifts, following the 2011-2015 drought.

Amount of water stored as snow

Less water

More water

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Below historical average

Above historical

average

Below historical

average

Scientists from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) expect to see an increase in ‘precipitation whiplash’ events in the region, with rapid transitions between extreme wet and extreme dry periods.

These extreme precipitation events pose a risk to dams, levees and canals, few of which have been tested against intense storms such as those that caused the Great Flood of 1862. By the end of the 21st century, the frequency of floods of this magnitude across the state is expected to increase by 300 to 400 percent.

Dams are at risk

During the winter of 2017, record snowfall in the Sierras caused a spillway to fail on the Oroville Dam, sending water spilling over the dam. Nearly 190,000 residents were forced to evacuate their homes. The man-made lake is the linchpin of California’s government-run water delivery system. It provides water for agriculture in the Central Valley and for homes and businesses in Southern California.

After the damage to the dam’s spillways, DigitalGlobe, a satellite imagery company, released images showing the extent of the damage.

August 2016

February 14, 2017

Lake

Oroville

Lake

Oroville

After torrential winter storms, water poured over the lake’s spillways, severely damaging them.

Emergency

spillway

Emergency

spillway

Low

water level

Overflow

damage

Melting brings trouble

Scientists from UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability and the Center for Climate Science predicted increased warming in the region will cause snow to melt faster. Also, more of the precipitation will fall as rain rather than snow.

Currently, half of the total water in the Sierra reservoir runs off by May. If greenhouse gases are not mitigated, by the end of the century we will see the water reserve halved 50 days earlier. This could pose problems in managing water in the reservoir system, which serves a dual purpose: it stores water for use in dry seasons, but also protects downstream communities against flooding.

Half of the total water stored in the snowpack is projected to run off 50 days earlier by the end of the century.

Measured runoff

1981-2000

Projected runoff

2081-2100

Jan.

Feb.

March

April

Runoff

midpoint

May

June

July

Aug.

Dec.

Water from precipitation is stored throughout the year.

The future of snowpack in the Sierras

If the pace of global warming remains unchanged, there will be 64 percent less snow in the Sierra by the end of the century, scientists said.

If the global community takes measures to curb climate change in line with the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement the loss in average springtime snowpack volume would be 30 percent.

Water content in the Sierra snowpack under different scenarios

1,000 mm snow water equivalent

No climate change

2016-2017 winter

800

600

Greenhouse gas

emissions reduced

400

200

Greenhouse gas emissions not

reduced by end of century