Archeologists Study the World’s Oldest Tree Carvings

Photo: National Parks Conservation AssociationThere’s something romantic about the image of two young valentines, in an idyllic pastoral scene, etching their initials in the side of a tree to commemorate their affection, but tree carving isn’t just for lovers. In a burgeoning field of archeological study, researchers are looking to some of the world’s oldest tree carvings, known as arborglyphs, to better understand the peoples and traditions of cultures past — and most are a lot more interesting than just a heart with an arrow through it.

Photos: Basque Library, University of Nevada, RenoAccording to archeologists, the of carving shapes and symbols into living trees has likely been practiced by civilizations throughout the world, though very few culturally modified trees dating back more than a few hundred years still remain. Since arborglyphs are etched into living wood, they’re lifespan is typically limited to that of the tree — so unlike petroglyphs, which can date back thousands of years, tree carvings are among the most fleeting artifacts of past cultures that exist.

Perhaps the most studied arborglyphs are the ones produced by Basque immigrants who left their native Pyrenees Mountains to work as shepherds throughout the western United States beginning in the mid-19th century. Because their occupation would have them alone for months at a time in some of the most remote forests, they took to perfecting the art of tree carving — leaving behind drawings and poetry delicately etched into the wood as living artifacts.

Photo: The Society of Environmental JournalistsThe nation’s foremost expert of arborglyphs is Basque history Professor Joxe Mallea-Olaetxe of the University of Nevada. Over the last several decades, he has recorded around 20,000 tree carvings across California, Nevada, and Oregon dating back to the turn of the last century.

“It’s mostly history. For me that’s what they are,” says Mallea-OlaetxeIf told the Sacramento News-Review. “We didn’t have these carvings, how would you know who was herding sheep on this mountain, for example. There is nothing written on that. The Basque country, being very small, and the Basque people being very few, it is important for them to know where everybody went and where they herded, how long, all of those things. And the only information comes from the trees.”

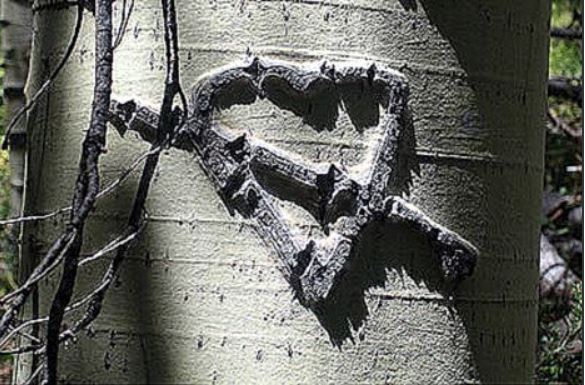

Photo: Ken ProperFor the shepherds, the smooth, white bark of aspens proved the best natural canvases. With a knife, or even a fingernail, the artist could scratch off a thin layer of bark to form words or images. At first, their carvings would be difficult to see, but in time the tree’s healing process darkens the markings, making them stand out against the pale wood.

“It is the tree who does the carving, not the herder,” says the Professor. “The herders did not really do this carving other than the very initial, and how it would look 20 years down the road, they had no idea.”

Unfortunately, since aspens typically only live around 100 years, most remaining examples only date back that far. Still, researchers have found even old arborglyphs in fallen and standing-dead trees.

Photo: University of NevadaWhile tree carving is thought of a lovers’ pastime, those studied by archeologists are quite different. The quality and subject matter of the arborglyphs ranges from simply dates and names to elaborate drawings of often explicit sexual imagery, but they all seem to point to the effects of solitude on the shepherds. To U.S. Forest Service heritage expert, Angie KenCairn, the aspen art reflects the deepest longings of folk engaged in one of the most socially isolating occupations.

Photo: Delirious Ramblings“Sometimes they just tear at your heart. They were lonely men. That’s obvious from the sheer number of women they drew. One carving reads, ‘Es trieste a vivir solo,’ (It’s sad to live alone). That’s tough. It’s why herding sheep isn’t a job that many people want to do,” KenCairn told Steamboat Magazine.

Professor Mallea-Olaetxe, who has devoted his academic life to documenting the arborglyphs, time is running for many groves where they remain. Wildfires, disease, and natural deterioration threaten the untold number of tree carvings yet to be assessed, threatening to destroy the living remnants of a cultural legacy stretching back for well over a century.

Photo: Alex WierbinskiAlthough there is much to learn from the history preserved in the aging arborglyphs, conservationists generally discourage others from carving trees. Aside from being regarded as ‘graffiti’ in many cases, the practice could also prove lethal to the tree. Deep gouges into a tree’s trunk, like in skin, makes the tree more susceptible to diseases and pests.

While the lonely shepherds at the turn of the last century may have perfected the art of tree carving, perhaps nowadays the most romantic way for young valentines to commemorate their love is to leave things as they are.

The same applies to tree-carving pranksters whose trickery threatens to throw archeologists off by a few hundred-thousand years.

Photo via Utah Wildlife Network

More on Art in Nature