Cities Should Think About Trees As Public Health Infrastructure

Planting trees is an incredibly cheap and simple way to improve the well-being of people in a city. A novel idea: Public health institutions should be financing urban greenery to support well-being and air quality.

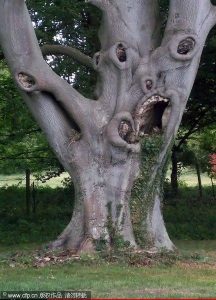

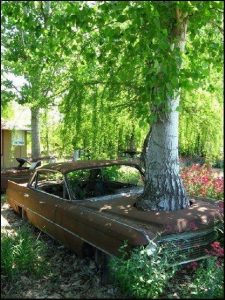

Think of a tree-lined street in the midst of a busy city. It feels like something of a treasure: hushed, cool, and sheltered from noise and sidewalk glare.

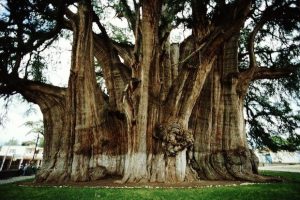

These leafy streets cannot afford to be seen as a luxury, argues a new report from The Nature Conservancy. Trees are sustainability power tools: They clean and cool the air, regulate temperatures, counteract the urban “heat island” effect, and support water quality and manage flow. Yes, they look pretty, but they also deliver measurable mental and physical health benefitsto concrete-fatigued city dwellers.

So with evidence to back up all the benefits of urban greenery, TNC set out to answer, in this report, the question of how cities can develop innovative financial structures and policies to plant more trees.

It’s a particularly pressing question now, because despite overwhelming evidence testifying to the environmental and health benefits of urban trees, their presence is declining in cities across the U.S. Around 4 million urban trees die or disappear each year, and replanting efforts have failed to keep pace, even though a 2016 study on California from the U.S. Forest Service found that every $1 spent on planting trees delivers about $5.82 in public benefits.

Because urban trees are often slotted into the “luxury” or “nice to have” category in city budgeting decisions–certainly less prioritized than public safety and infrastructure maintenance–funding is often inadequate, and fails to treat trees as a long-term investment, and certainly not one that can deliver health benefits. The standard rate of investment in trees is around one-third of a percent of a city’s budget, says Rob McDonald, TNC cities scientist and lead author on the report. “It’s not enough to just talk about why trees are important for health,” McDonald says. “We have to start talking about the systemic reasons why it’s so difficult for these sectors to interact–how the urban forestry sector can start talking to the health sector, and how we can create financial linkages between the two.”

TNC estimates that coming up with the capital necessary to maintain our current urban canopy, and expand it to the point where it creates consistent health benefits, would require an annual investment, on average, of $8 per person–a sum that would just about double current municipal tree-planting budgets. That figure is hypothetical and meant to suggest not that funding for trees should actually come from U.S. residents, but that the project is well within the scope of affordability.

What if, McDonald asks, that funding could come from the health sector? A 2013 study found that urban trees remove enough particulate matter from the air to create up to $60 million worth of reductions in healthcare needs at the city level. If public health spending in cities increased by just 0.1% or $10 per person, that would create enough public investment to finance the maintenance and expansion of urban forests and deliver the resulting health benefits. Again, this is just a rough model, but the case for treating trees as infrastructure that supports public health, and eventually could reduce the need for spending in that sector, is strong.

There’s a wrinkle in this idea, McDonald says, and it derives from the fact that while cities are the agencies that pay for trees, they do not necessarily oversee health spending. That often falls to the state, or large local insurers. “But one big goal of this report is to get a variety of health agencies to see that they should be participating in the urban greening conversation,” McDonald says. In fact, the Affordable Care Act has created a $16 billion prevention fund to be funneled into communities working on widespread health-supportive initiatives; urban trees, McDonald says, could fall under that purview. And Kaiser Permanente, a large insurer in Northern California, announced last year a $2 million investment in public parks in low-income communities in the Bay Area.Diversifying funding sources for urban greenery–and casting trees as a health investment–could also begin to close the socioeconomic gap in access to parks and green space, too. A 2013 UC Berkeley study found that compared to white people, black people were 52% more likely to live in sparsely shaded, and consequently, much hotter, parts of the city, and have less access to green spaces. While initiatives like New York City’s Million Trees NYC have made a concerted effort to create more equity when it comes to green space in the city, often, trees are added to neighborhoods only at the behest of community groups. Those with more financial resources, McDonald says, are often more likely to make and be granted those requests.

Creating greener cities cannot be the responsibility of the health sector alone; McDonald says it will be crucial for urban forestry departments to more fully integrate the health benefits of their trees into messaging and goals in order to break down city agency silos and communicate more effectively with urban health and planning departments. And of course, as more and more cities develop strategies to create resilience against climate change, a healthy urban canopy will be a hugely necessary component.